The Lacora L-40 radio was a relatively popular low-cost model in 1950s Spain.

Thanks to its small, compact size, light weight, and relatively low price, many units were sold.

Lacora itself was not a radio manufacturer per se, but it did produce various radio components, especially the cabinets.

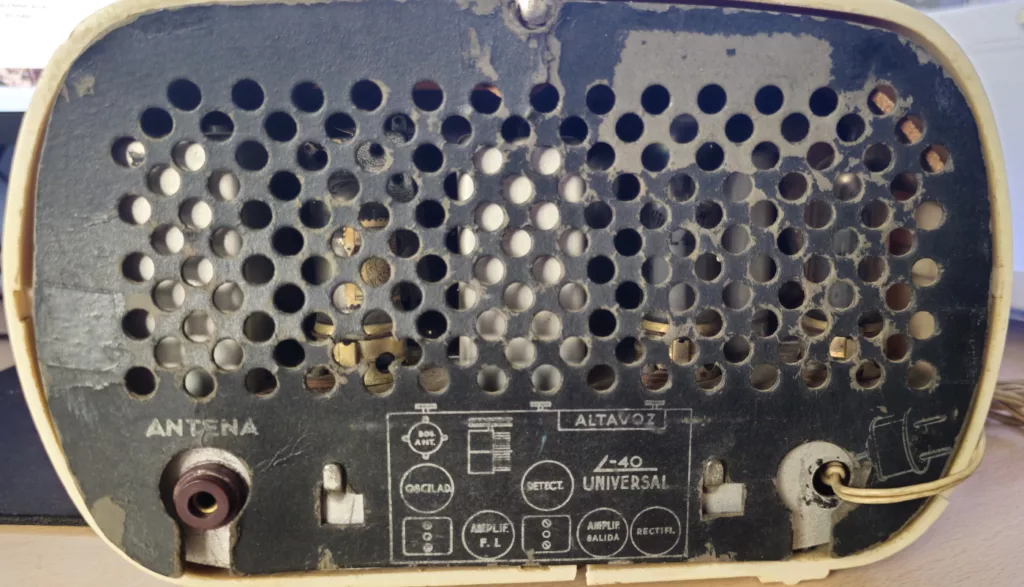

So, in the 1950s, they sold the cabinet as a kit, which they called the L-40. It included all its accessories and a basic superheterodyne receiver circuit with medium-wave and short-wave bands, in cabinets of different colors.

Many other manufacturers bought the Lacora kit in bulk to later offer their own versions. This is why there are various differences under the same name (different colors, slight circuit changes, etc.).

One of them was Radio Bertrán with its KIT 201. They offered their own more compact and easier-to-assemble coil block than the original Lacora one.

In my case, I managed to get hold of two Lacora L-40s, in brown and white, although unfortunately the white one was damaged in transit:

Since the brown one was in better aesthetic condition, I decided to repair it, using the electronic parts from the white one as spares if needed.

Features of the Lacora L-40 radio

The original valves in the Lacora L-40 kit are:

- UCH42: As mixer/local oscillator.

- UAF42: As intermediate frequency amplifier.

- UAF42: As detector/audio preamplifier. In some variations of the original circuit, the UBC41 is used instead.

- UL41: As audio power amplifier.

- UY41: As high-voltage rectifier.

As you can see, Rimlock valves are used, which were popular at the time. It also features a universal-type circuit (similar to, for example, the Philips BE292U) to save on the size, cost, and weight that a power transformer would entail.

It’s worth remembering that universal-type radios are dangerous. Since they lack a power transformer, one pole of the mains is connected to the chassis. This means that touching the chassis or any metal part carries a significant risk of electrocution—equivalent to sticking a finger in a socket.

Normally, the user only touches plastic or Bakelite parts that are insulated. However, the danger of accidentally touching a metal part was always present.

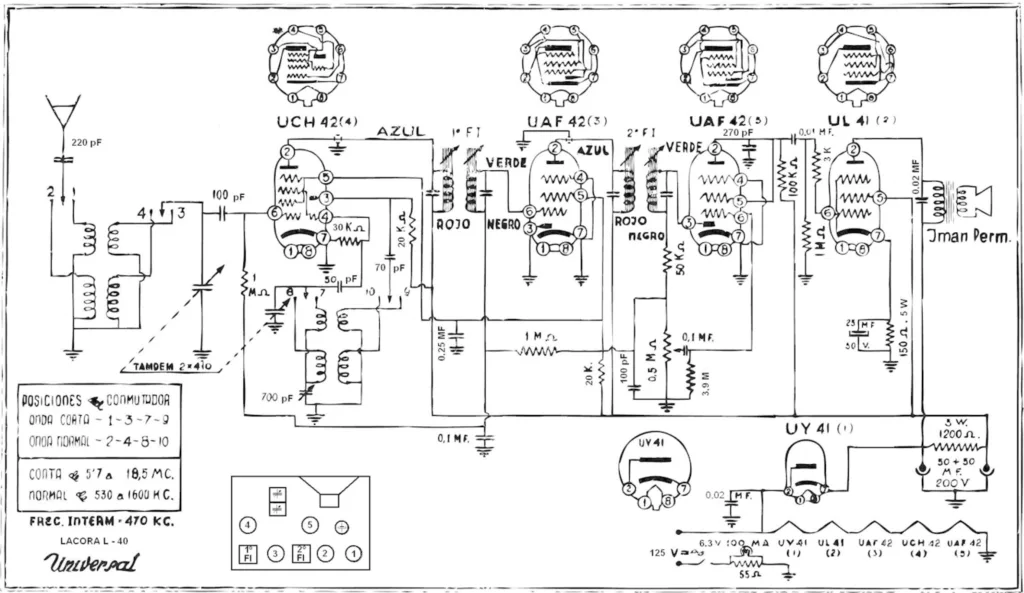

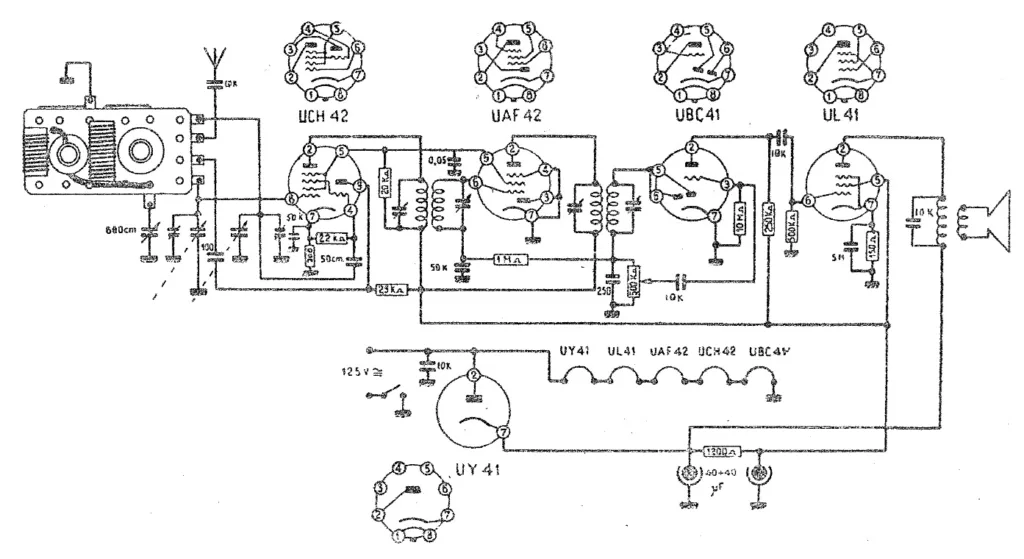

Circuit diagram analysis

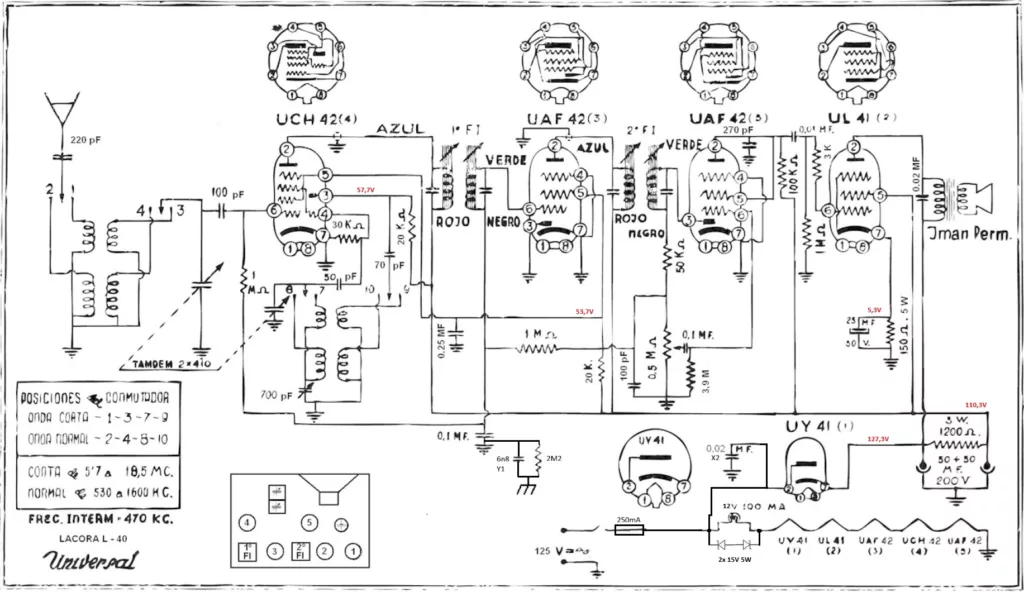

Regarding the schematic:

It’s a fairly standard and simple design. Like most radios of this era, and especially universal ones, it’s designed to run on a 125V mains supply.

Today, you have to be careful because if connected to modern 230V, the valve filaments will burn out.

As a curiosity, the dial bulb illumination system is one commonly used at the time. A shunt resistor is used, forcing all the filament current and high-voltage current to pass through the bulb.

This is done because if the dial bulb were used directly, it would burn out due to excess voltage when turning on the radio with the other valves’ filaments cold.

The problem is that once in normal operation, the bulb receives less voltage than it should, making it dimmer. To somewhat compensate, all the high-voltage circuit current is also forced through the bulb.

This provides a bit more voltage, but still far from the nominal 6.3V needed for full brightness.

Repairing the Lacora L-40

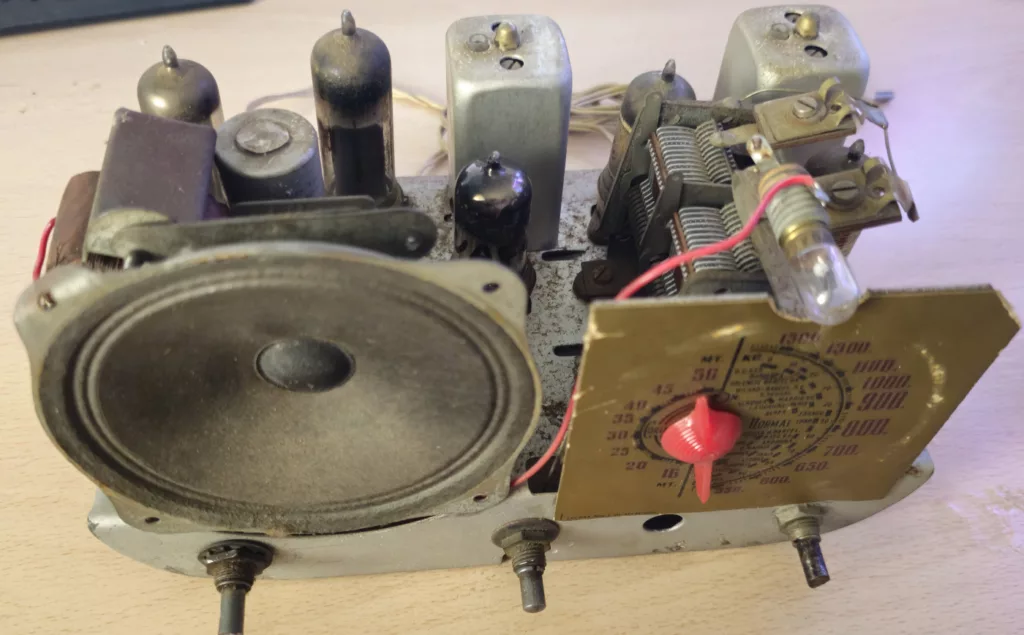

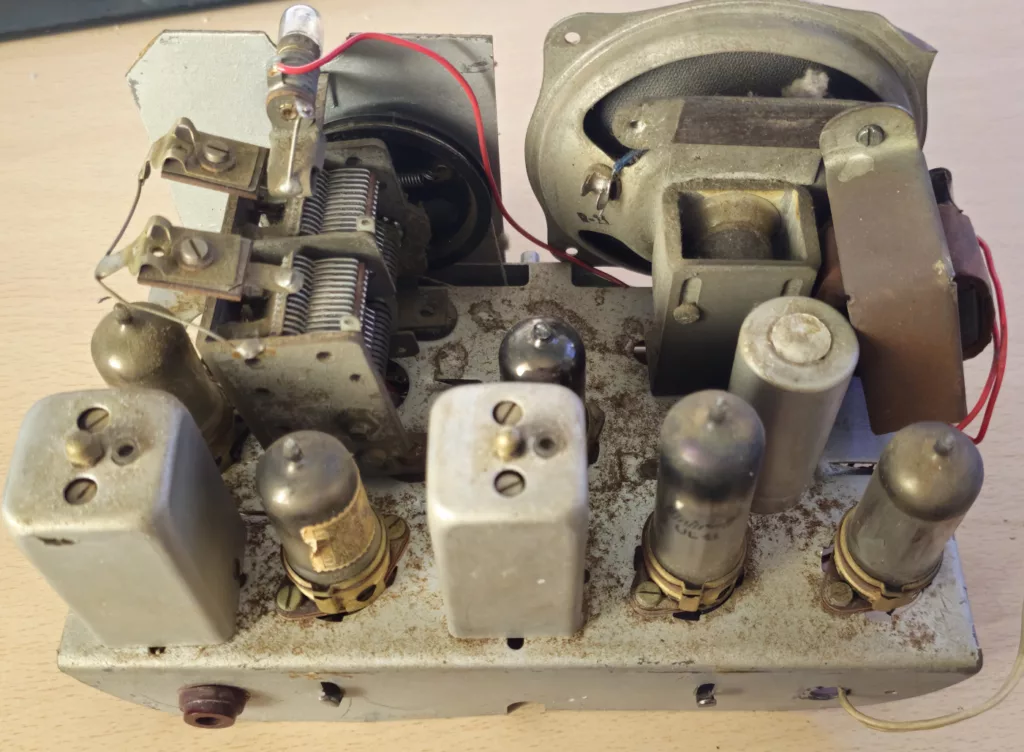

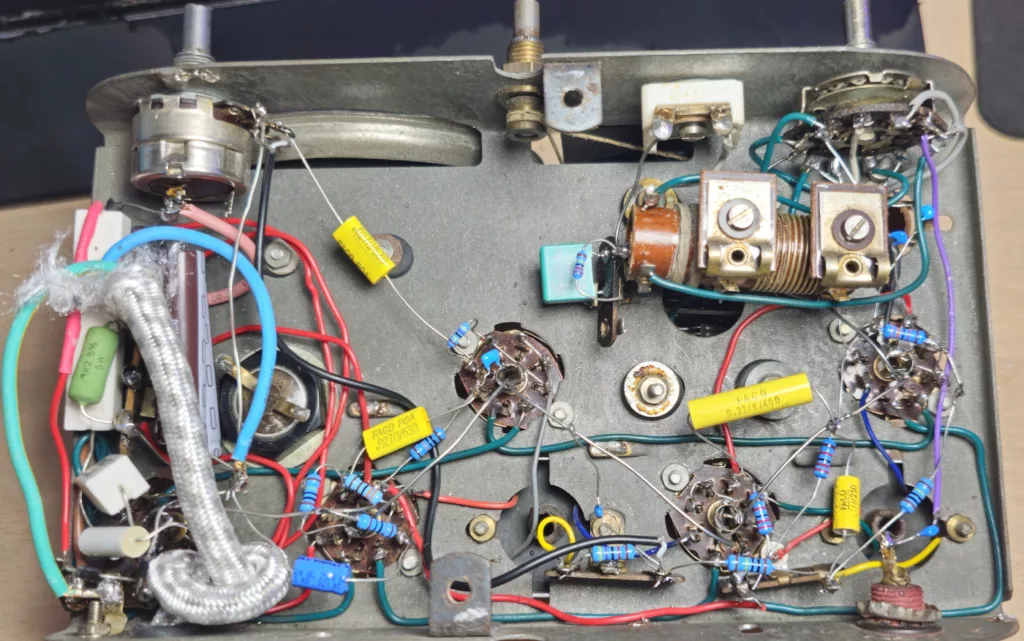

The first step in any repair is always to assess the overall condition of the circuit:

From this initial inspection, I draw these conclusions:

- The radio has been partially restored by someone. They replaced the electrolytics and the 10nF paper capacitor on the UL41 control grid to prevent leakage from the original capacitor from destroying this valve. However, other paper capacitors were left untouched.

- The 6.3V bulb is incorrect—it should be 100mA, but this one is 800mA! That means it receives a ridiculously low voltage and won’t light up.

- The original output transformer has been replaced with another that, while functional, is too large for the original speaker space. That’s why it’s been awkwardly hung on the side.

- The variable capacitor, though not visible in the photo, has one slightly bent plate. This causes a short circuit in certain dial positions.

- The antenna connector is glued to the chassis with hot-melt silicone because the thread is damaged.

As an interesting note, this radio isn’t a pure Lacora L-40… It’s actually a mix of a Lacora L-40 and a Bertrán 201 kit! It’s given away by the Bertrán components and the coil block matching their specific schematic:

After seeing this, considering the overall condition and that it’s a simple radio, I decided to rebuild it from scratch, using the correct original L-40 coil block borrowed from the white radio, its proper transformer, etc.

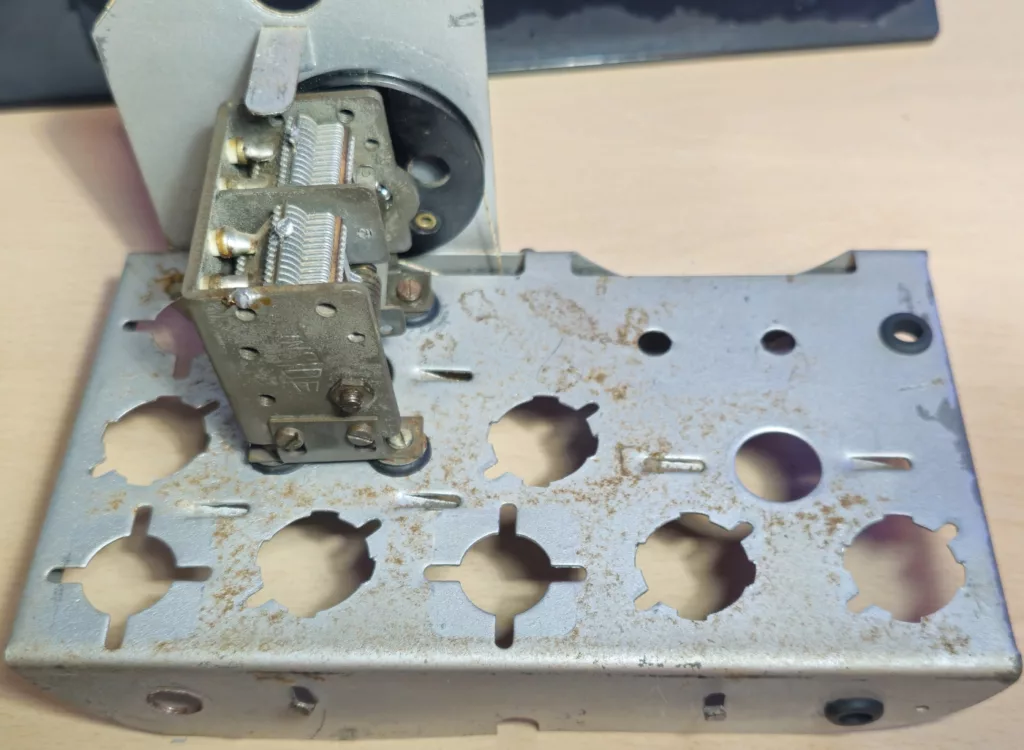

Disassembling the Lacora L-40

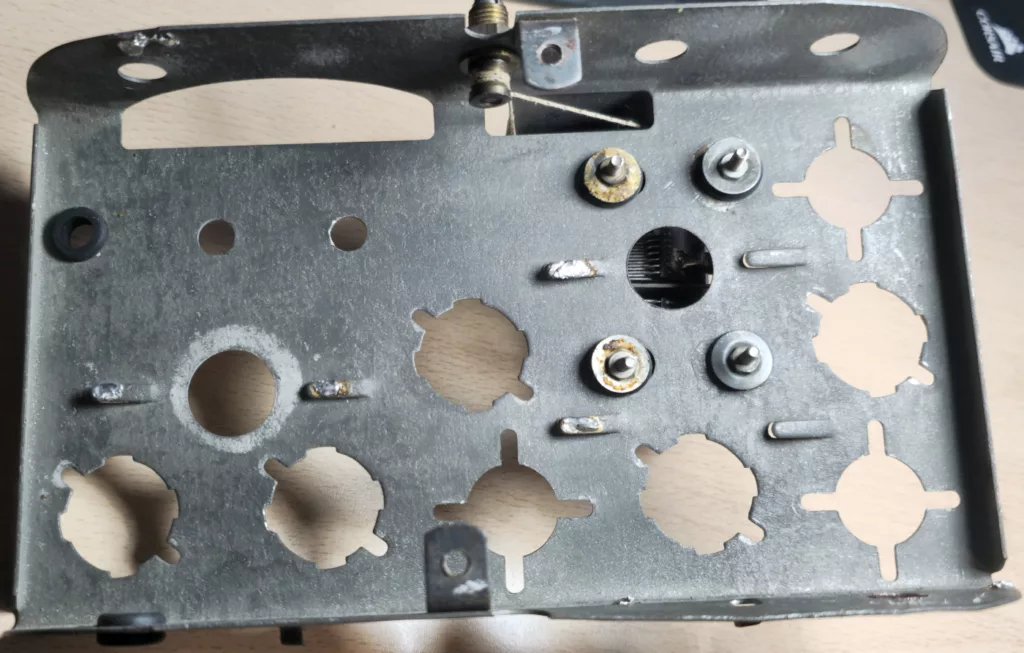

The easy part of rebuilding a radio from scratch is taking everything apart. In a short time, the chassis looks like this:

Then we can start the actual assembly. But first, as a safety improvement, I decided to use a ground bus independent of the chassis, connecting the bus to the chassis via a high-quality Y1 capacitor. This ensures that in case of failure, the chassis will never short-circuit and expose itself to mains voltage.

First, clean the chassis as much as possible and install the variable capacitor with its insulating rubber grommets. These are important and, in 100% of radios, have deteriorated over time.

Their main function is to prevent chassis vibrations from reaching the variable capacitor, avoiding microphonics. Additionally, in this case, they also electrically isolate the variable capacitor from the chassis, which is necessary when using a floating ground bus.

The rest of the assembly is straightforward by following the schematic, and in a few hours, it’s fully complete (though with some modifications I’ll mention later):

After aligning the radio with a signal generator, it works perfectly—repair complete!

Schematic improvements

Taking advantage of the ground-up rebuild, I decided to implement the following improvements, which are always worthwhile for any radio of this type:

Electrical safety improvements

The first improvement is a floating ground bus separate from the chassis for better safety. This ground bus is connected to the chassis with a 2.2MΩ resistor in parallel with a 6.8nF Y1 safety capacitor. This is necessary because the chassis must be at ground potential for RF frequencies while blocking as much of the 50Hz mains frequency as possible, which is achieved with a capacitor of this value.

A new grounded power cord has also been added. The ground is connected directly to the chassis, so if any leakage occurs from the radio circuit to the chassis, it will trip the RCD (residual current device) before the chassis becomes live, avoiding the associated danger.

As an extra benefit, this allows the RF input circuit to be grounded, improving reception compared to the original setup with just a single wire antenna without ground reference.

A fuse has been added at the input to protect the circuit in case of failure.

Circuit improvements

The original dial bulb circuit has been changed. First, the original bulb was replaced with a 12V 0.1A one (more readily available today), and the shunt resistor method was eliminated to place it in series with the other filaments.

The difference is that to prevent the bulb from burning out during startup, two 5W back-to-back Zener diodes with a voltage slightly higher than the bulb’s were added. This protects the dial bulb during power-on.

Additionally, this ensures the bulb receives its correct voltage, which didn’t happen in the original schematic.

Finally, approximate voltages for each part of the circuit have been added to the schematic.

However, there are a few more modifications, like the one I ultimately made: conversion to 230V for modern mains voltages.

Conversion to operate on 230V

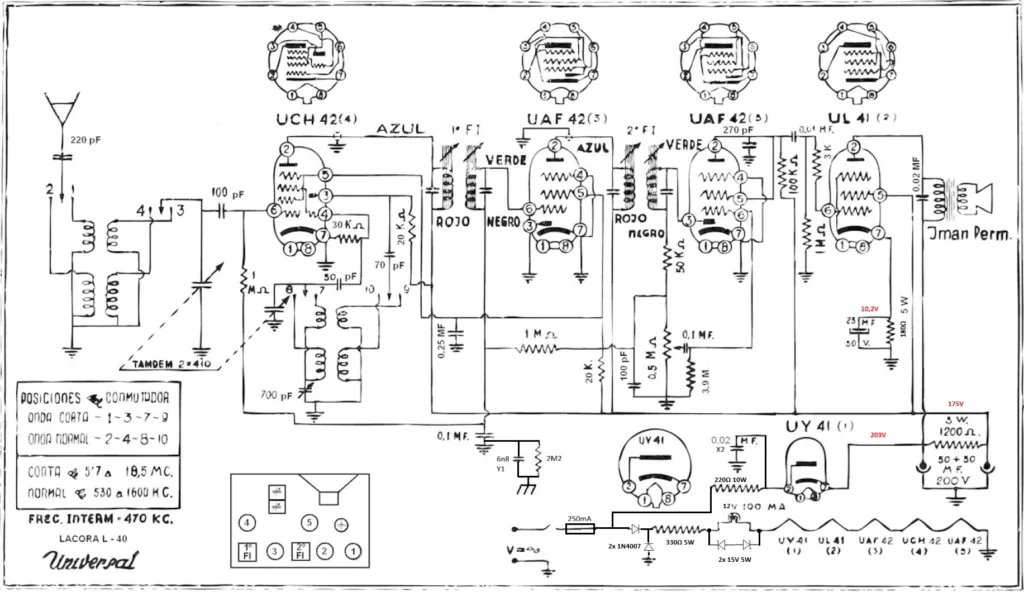

The final schematic, including the conversion, is as follows:

In general, the previous improvements are retained, but with additions related to the conversion.

Rectifier section conversion

First, a 220Ω 110W resistor must be added in series with the UY41 anode. This wasn’t necessary at 125V, but at 230V, it becomes mandatory to limit the peak current in the rectifier valve during normal operation.

Since we now have higher voltage, the output stage needs slight adaptation. To do this, increase the UL41 cathode resistor from 150Ω to 180Ω. This provides the correct bias voltage for the new high-voltage levels and also delivers more audio power to the speaker. The rest of the circuit requires no changes.

Filament circuit conversion

The filament section has undergone the most changes. To avoid wasting so much energy in the voltage-dropping resistor, I used the trick of a silicon diode to clip half the mains waveform, so the resistor only needs to dissipate about half the power it would otherwise.

When using this trick, note that the RMS voltage after the diode will be Vin × 0.707, which for 230V is 162V. The filament resistor is therefore calculated based on that value, resulting in approximately 330Ω and 5W.

The diode connected to ground serves as a protection diode. If the filament diode fails shorted, this diode will conduct, causing a short and tripping the input fuse, protecting the filaments from overvoltage in case of such a failure.

With these modifications, the radio works perfectly on 230V and, moreover, much more safely than originally. I encourage you to try these improvements on this radio or any with a similar schematic.